Myths of Low Back Pain (LBP) and Evidence-Based Realities

Low back pain is everywhere on social media—but much of what’s shared is a far cry from best practices. Platforms like X, TikTok, and Instagram thrive on the hype of mechanical “fix-it” approaches, leaving little room for evidence-informed, person-centered care.

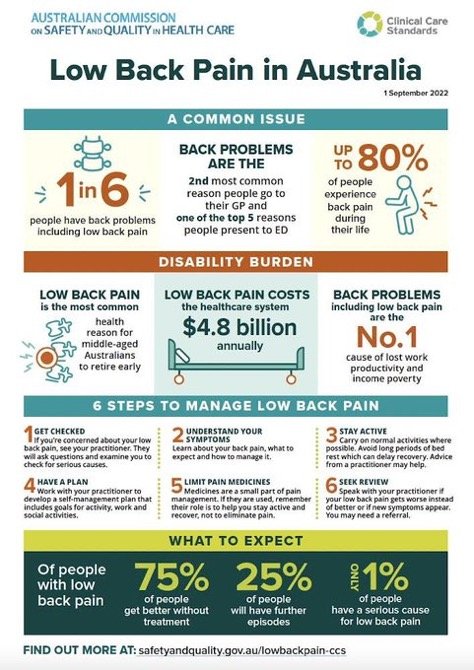

Surprisingly, you’ll rarely see references to key resources like The Lancet’s three-part series on low back pain, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) updated guidelines, or the practical Australian Clinical Care Standard. This gap contributes to the persistence of “zombie myths” about low back pain—beliefs that refuse to die.

80% of people will experience some level of low back pain in their lifetime. Back pain is the number 1 reason for missed work.

Why Do These Myths Persist?

Many patients acquire their beliefs about low back pain from outdated ideas and overly simplistic “quick fixes.” The reality is that most acute or subacute LBP is mismanaged. People are often labeled with nocebic diagnoses and subjected to evidence-discordant treatments promising a rapid cure. This outdated model neglects the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors involved in pain.

Low back pain triage is important for proper management of the injury. Getting people active as soon as possible is crucial to minimize disability.

The Alternative: Evidence-Based, Person-Centered Care

Best practices emphasize reconceptualization, reassurance, and reactivation—helping patients understand their pain, stay active, and co-create a management plan. For many chronic pain sufferers, these elements have been missing in their care.

An optimal approach includes:

Shared Decision-Making: Open discussions about the uncertainty of the pain’s trajectory and reassurance about safe activity resumption.

Personalized Planning: Developing a plan based on a gap/needs analysis of the patient’s goals and capacities.

Continuous Learning: Staying updated on evolving evidence to improve care and challenge outdated priors.

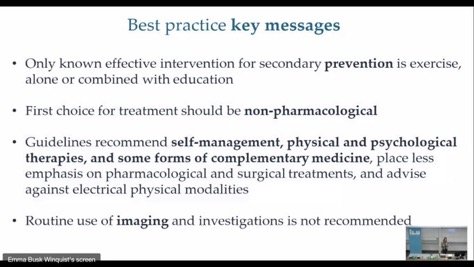

What Do Guidelines Recommend?

Current guidelines dismiss painkillers and bed rest as outdated remedies. Instead, they advocate for:

Self-Management: Movement and psychological strategies to address stress and barriers to recovery.

Physiotherapy: As a second-line approach to support movement and activity.

Drug Therapy: Reserved as a third-line intervention for persistent cases.

When dealing with low back pain, rehabilitation exercise is considered best practice. Conservative management is recommended when treating low back pain.

Breaking the Evidence-Practice Gap

For the majority of people with back pain, imaging findings are rarely predictive of pain severity. Yet, patients often receive diagnostic labels that create fear and avoidance behaviors—which, in turn, worsen their pain. This evidence-practice gap is a “super wicked crisis” in care that demands urgent attention.

To address this, clinicians must embrace systematic approaches:

Determine What Matters: Identify the factors most relevant to the patient’s experience.

Measure What Matters: Use evidence-based metrics to assess these factors.

Change What Matters: Co-create a plan to improve the patient’s outcomes and empower self-management.

When managing low back pain or injury we need to make the correct diagnosis of the problem, then set a movement baseline, to allow us to make the appropriate changes.

The Call to Action

It’s time to move beyond mechanical “fixes” and embrace a holistic, evidence-informed model for managing low back pain. As evidence evolves, so should our practices. Let’s replace myths with meaningful care and transform the “call for action” into real change.